Reading and writing stream of consciousness (SOC) is not for everyone. For someone who has never read SOC, attempting to understand its flow and follow its thought-pattern could be extremely difficult. Writing SOC isn’t any easier. It takes much practice to master the art.

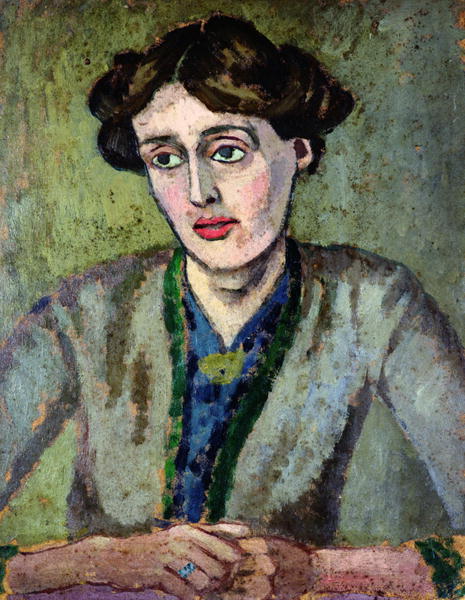

There only have been a few experts who have mastered stream of consciousness writing. Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, William Faulkner, and a handful of other writers have written this way. Continue reading to see how they crafted their SOC and how you—the writer—can develop your own style.

Through my research writing this post, I found it has been easier finding criticism on stream of consciousness than actual tips to write stream of consciousness.

With the virtual non-existence of SOC in today’s literary landscape, I would say that the majority of writers feel the same way as myself.

SOC is such a daunting, exhaustive task that it takes a special writer not only to complete it but to craft it in a way that is appealing to the reader. Perhaps that is why SOC is hardly around anymore. Good luck, I say.

These days SOC is used, however, very sparingly (if not at all) within genres other than literary fiction. Even literary fiction has seen a decline in SOC for third-person POV’s.

However, when correctly written, SOC provides great storytelling. It allows an insight into the mind of a character unlike anything else in literature. The interior monologue SOC has makes for the closest method to understand the way someone thinks. In other words, if done right, SOC provides the reader with empathy into the character.

Understanding Stream of Consciousness

The term ” Stream of Consciousness” is not truly a literary term. We hear it so much in the literary world, we might think it originated from great literature. It did not. In fact, the term grew from psychiatry to describe how patients’ thought patterns could be understood.

It made its way into the literary world during the early part of the 20th century. James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and others perfected the art so well that the term became independent from its originating source. For many writers, SOC is difficult because the hand doesn’t type or write as fast as the mind thinks, making it hard to write down thoughts as they come. However, it can be done.

For writers to produce an SOC novel, they must first understand the term. Psychologists coined it “Stream.” But why? Why not use a different term? They decided upon the term stream because of its obvious implications to an actual flowing body of water.

Although the body of water (stream) heads towards the same point as anything within it, the stream has the freedom to venture anywhere it wants.

And when you compare and contrast a person’s thought process to this, it makes perfect sense. Without diving into the ocean of psychology, our brains have the ability to think of numerous things at once. The thoughts bounce around as we are physically doing other things. It is very complex.

The same applies to SOC novels. SOC is so much more than a simple interior monologue. SOC bounces around from thought to thought, some random, some important. But they are all important to the progression of the story—and more importantly, the character.

“Stream of consciousness is not a technique for its own sake. It is based on the realization of the force of the drama that takes place in the minds of human beings.” —Robert Humphrey

Writers like Faulkner and Woolf have opened up literature by applying mental functioning to the narrative. They have gone far beyond the simple point of view. What they have explored and successfully written as an example of how complex and near-impossible it is to understand the psychic existence of another.

Stream of Consciousness Techniques

Attention all writers! Pay attention to this section.

We will now discuss some techniques, direct and indirect monologues, that form the basis of a stream of consciousness narrative.

Personal Note about Stream of Consciousness!

- Some naive literary critics and rookie readers of fiction might categorize true SOC with the general interior monologue they would read in everyday fiction. I disagree with this. First-person narration—for the lack of a better word, is basic and general. The first-person POV we typically see in storytelling tells a narrative from an overarching perspective that includes certain elements, such as setting. When regular first-person does dive a little deeper in a character’s interior monologue, it does so briefly to make a point before jumping out again.

- REAL stream of consciousness does not jump out. EVER. Novels with SOC as a perspective use tight, close interior monologue all the way through the story. It focuses on the thought patterns—sometimes irrelevant to the story or scene—to describe what the character is thinking. The entire novel is told this way with a plot interwoven within its close narration. True SOC does not allow for the typical coherency we see in today’s storytelling.

- True SOC is the closes thing in fiction we can get to a detailed look into a person’s mind.

Now let’s keep goin’…

Interior Monologue

Direct

- no author influence in character’s thoughts

- this is very tricky and only for writers of a particular caliber. It means the author is 100% able to write from the thoughts of the character while 100% being not involved. If you can do this, then you might be the next Woolf or Joyce.

- no “he said” or, “she thought”

- this is referring to the rules/guidelines of using SOC in first-person. For example, when you are holding a conversation with another person, I doubt you are mentally jotting their dialogue tags.

- the character is not speaking to anyone

- Remember: this is 100% only in the mind of the character. Unless you are merging SOC with a mind-reading plot, don’t do it.

- the first-person point of view (I, me, we, us)

- there isn’t any problem using these pronouns while in SOC

- does not focus on irrelevant topics

- being that reading SOC is difficult enough for your average reader, having the character go off on random tangents about topics that are unwarranted for the story will only do your story damage.

- NOTE: SOC is beyond normal 1st person

- SOC is nothing you have read in 1st person before. You will know SOC when you read a book that uses it. It is a far deeper and more personal narrator than the normative 1st person you usually read. It is, hence like the title, direct.

Indirect

- the author is involved in the character’s psyche and the reader.

- whereas direct SOC acts independently as if without a reader, indirect flows more coherently (usually) because the author is there with a purpose to guide the reader.

- the author is a guide

- the author knows he or she wants to tell a story using SOC but chooses to not dive in too deep to the character’s psyche in danger of losing your attention. Think of indirect monologue as a shortcut version of SOC and omniscience.

- typically uses punctuation

- not all the time, though. There are many instances where indirect monologue doesn’t use punctuation, but it isn’t known for it that often.

For example, let’s look at Virginia Woolf’s most famous novel, “Mrs. Dalloway”:

“Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself. For Lucy had her work cut out for her. The doors would be take off their hinges; Rumplemayer’s men were coming. And then, thought Clarissa Dalloway, what a morning—fresh as if issued to children on a beach.”

Without going further (because we don’t need to), we can analyze how Woolf installed SOC in just these few sentences. In contrast to other uses of SOC where limited punctuation is used, Woolf writes freely using semi-colons and exclamation points.

But more than that, the first 3 sentences quickly introduce 3 characters in a very vague way. We don’t know who they are, but we know they must be connected somehow. In contemporary writing, the introduction of characters lingers, with whole scenes to flesh them out. Woolf, using SOC to jump from thought to thought, jolts our expectations. It isn’t until the last sentence that we see the aforementioned Mrs. Dalloway appear again—now with a first name to have her appear more relatable—in her thoughts.

The Problem with Stream of Consciousness

I believe the problem with SOC roots more in the reader than the writer, hence the lack of popularity it has today.

A writer can learn SOC and a good writer can learn it quickly. However, reading an SOC novel, unless one has a history reading it, is quite difficult for beginners. The masters like Woolf and Joyce, unload themes and subtext within the SOC so heavy that only a trained eye can pick up the messages. A novice reader may not catch the information, leaving them without the full interpretation of the story.

To combat this is to write SOC yourself while studying the greats. I suggest beginning with notes from psychiatrists about stream of consciousness. After all, that is where it originated. Look into what Sigmond Freud wrote about SOC. Read easier stories like “Mrs. Dalloway” and “To the Lighthouse.” See how Woolf structured her sentences, how she jumped around, using memories. Once you feel you are ready, try a more difficult writer, like James Joyce. His “Ulysses” is not for a beginner.

For more insight on how to write points of view, you should check out my post.

And if you are a writer looking to get your story edited, check out my services page for prices. If you need custom work edited for a large novel, send me a message to discuss custom prices.

And if you want to amplify the suspense in your short story or your novel, you can purchase my eBook here.

Get edited.

~M