The argument regarding the definition of literary fiction is well-known in the world of literature. Unfortunately, pinning down exactly what literary fiction is, never truly reaches a solvable destination with any accurate understanding. There are several reasons for this, mainly because literary fiction is not entirely different from commercial fiction, except that it sometimes may contain more or less specific features that separate one from the other.

Follow me as I provide the definitive answer to literature’s most notorious debate. By comparing and contrasting the subtle traits of how literary fiction uses plot, deep characterization, social and political themes, and even the title and cover design of the book covers, this article will explain—once and for all—literary fiction.

Emphasis on Character

Anyone doing his or her research on this subject will undoubtedly see characterization as one of the top priorities to defining literary fiction. And it should be. While in commercial fiction, a character is and can be expressed well, it seems too often to take a back seat to the plot.

Literary fiction, on the other hand, celebrates characterization. Usually, right from the beginning, the author will provide a history of specific situations that create the mindset for the characters to follow (Mystic River). From there, you will get to know how and why the characters make their choices throughout the novel. These choices define who they are.

The reader will discover why the husband decides to wake up a half-hour earlier than his wife. You will find out the real reason the main character’s sister embezzles cash from the account at her church. And as a result, you will sympathize and empathize with them, even if they are not wholly good.

These in-depth characterizations will not simply be a one or two sentence fling. Instead, literary fiction will dive into the senses, investigating the character’s opinions through detailed inner monologues and even dream sequences that will bring forward a grand level of understanding to the reader. By the final page, the human condition will have been examined from multiple angles.

Q. But why is knowing the character so important?

A. Because literary fiction is written with a purpose to allow maximum self-reflection for its readers.

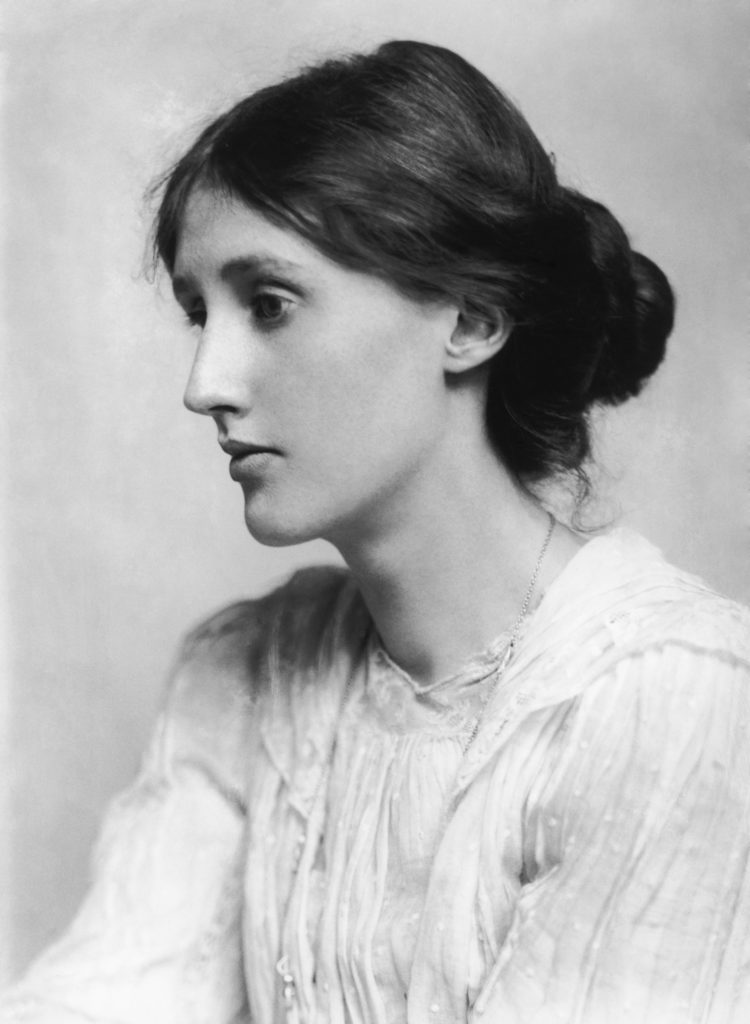

That is why characterization is written so carefully. By the end of the narrative, not only should the reader know the characters, he or she should know a little bit more about themselves. Virginia Woolf, perhaps the most talented writer of literary fiction to have walked the Earth, was a master at displaying characterization through her prose. When you reach the last page, you understand Mrs. Dalloway’s stress to throw a party.

Whereas commercial fiction provides insight into characters as well, literary fiction gives the reader a chance to analyze themselves and then bring a more empathetic perspective to the world.

Categorization

Comprehension of the name and what it represents is a good way to decipher the conversation.

“Literary” by all intents and purposes conjures an element of educated, professional—and dare I say, noble—characteristics. Because literary fiction bases its narrative concerning the human condition, it promotes itself to a crowd who enjoys serious scenarios. You will likely find those who enjoy the beautiful poetry of Frost as those who also schedule their lives to lose themselves about a husband’s mid-life crisis depicted within the pages of literary fiction.

Because literary fiction bases its narrative concerning the human condition, it promotes itself to a crowd who enjoys serious scenarios. You will likely find those who enjoy the beautiful poetry of Frost as those who also schedule their lives to lose themselves about a husband’s mid-life crisis depicted within the pages of literary fiction.

Author Justin Cronin acknowledges the difference between literary and commercial fiction:

“Literary fiction is fiction written to be respected and commercial fiction is fiction written to sell,” Cronin says in a YouTube video.

The “respect” attribute of literary fiction comes from many different things: poetic prose, profound exploration of character, modern and serious themes, all with the result of internal discoveries and changes to the character. Commercial fiction’s ability to “sell” hits a different mark in literature. If appealing to the masses (selling!) is commercial fiction’s main drive, then it might consist of similar traits of literary fiction, but they will be watered down with a spotlight on external goals and accomplishments.

A big mistake in defining literary fiction is that readers tend to categorize it the wrong way, leading to this never-ending debate.

A good way to establish literary fiction is deciding what it is NOT:

- 99% of the plot center around an external goal (i.e. terrorist plot).

- You can’t empathize with the characters.

- The prose is straightforward.

- The themes are thin.

- The ending finishes nicely without any ambiguity.

If you answered mostly YES, then chances are what you had read was not literary fiction.

Prose

One of the obvious signs of literary fiction is the beauty of its sentences. Many times, the way a poem flows from line to line, with its gorgeous description and effortless cadence, is the way an author’s prose glazes the page in literary fiction.

Commercial fiction, most times, uses a straightforward approach to its sentences. These sentences will be, typically though not all the time, medium in length. Long sentences, with many commas, tend to reside in the literary genre. The vocabulary is usually of a higher-caliber, not ordinarily seen in commercial-ish books. Why? Because readers of literary fiction are commonly those who enjoy the beauty of a well-made sentence. Readers of commercial fiction tend to focus on the sentences progressing the plot.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Michael Cunningham’s magnum opus The Hours and Justin Cronin’s Mary and O’Neil have some of the most elegant prose ever written by mortals.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Michael Cunningham’s magnum opus The Hours and Justin Cronin’s Mary and O’Neil have some of the most elegant prose ever written by mortals.

However, Ernest Hemingway and his famous usage of minimal and direct sentences seem to break this rule. (Though, there were many times he used long sentences!) Hemingway ushered in a new form of prose at a time when other great authors chose to expound with grand sentences.

Was Hemingway’s prose beautiful? No.

Then how could his prose fall under literary fiction? He wrote literary fiction because of his serious themes.

Themes

Whereas you will have love triangles in romance novels and twist endings in mystery novels, literary fiction brings on heavy themes of social issues, class, and political turmoil.

*Note: When I mention political, I am not referring to genre-thrillers with political plots.

No, what I am discussing is the underlying themes of social and political concerns. Maybe the most notorious would be George Orwell’s Animal Farm. This fantastic novel dives into social and political concepts with subtext spilling from each page as the animals battle for hierarchy.

True literary fiction takes these themes (any themes, really) and uses them in a fashion that refuses to directly confront them. Rather, well-written literary fiction uses themes as a background and sub-textual force that challenges the characters of the novel. It is the characters who must endure and overcome these themes at the end of the story, thereby completing the entire picture of what the author was intending.

Subtext

By now, subtext should be a common word in the Rolodex of a fiction writer. The definition is in the word itself: Sub, meaning under. And text, meaning the written word. You could think of it similar to when someone says to “read between the lines.”

The subtext, for the lack of a better word, is nothing more than implications or insinuations and is the close cousin to the theme. Usually, if written correctly, the subtext and theme will appear naturally.

In literary fiction to qualify under the official “literary” term, a writer should study subtext and learn how to apply it intelligently towards character motivation—especially dialogue. Without a doubt, the subtext is detrimental when having a conversation in fiction. You do it every day with your friends, your family, and your coworkers. Sarcasm is a form of subtext. Most jokes have a subtext in them.

When answering a question directly or stating facts without opinion, subtext doesn’t work—it can’t work. For subtext to thrive in fiction, a specific situation needs to apply and the characters in that situation must relate and react with each other by using subtext.

For example, the abovementioned novel by Orwell displays a superb subtext. In Animal Farm, the animals engage together as if a political system. There is an established hierarchy among the animals and they begin their own rules. Eventually, there is a power struggle. By the end of the novel, the animals ironically resemble the humans from whom they revolted. Animal Farm works wonderful, even though Orwell wrote it close to a century ago. That is because the social and political subtext Orwell uses is universal. If Orwell had made a straightforward political story with humans instead of animals, it might not have worked as well.

Bleaker Results and Ambiguity

In general, the greater part of literary fiction leans towards a more realistic, and therefore, darker side regarding the fates of the characters and situations. The possible reasoning behind this is that it is not a visual medium and will not have to portray any violent or taboo subjects. The reader gets to make that up in their own minds because literature is purely a psychological pastime. And, through my travels, I have noticed that the majority of literary genre readers prefer darker/realistic conclusions.

The literary fiction crowd expects the characters to suffer the consequences or benefit from justice. These final moments in literary fiction usually do not contain Mexican-standoffs, bombs, and epic monologues from a dying villain.

Endings in literary fiction typically leave the plot open to interpretation. More often than not, the ambiguity is calm and peaceful. Sometimes, the final moments linger on a description of a setting or an object. Some literary fiction will end with the thoughts of a side character the reader may not have considered relevant (Revolutionary Road).

Q. But why would leaving the finale without total closure be acceptable?

A. Because literary fiction is the closest representation readers get to real life.

And in real life, events rarely finish the way we want or the way we expect. Open endings allow the reader to decide for themselves how the story ended. And in some regards, that makes more sense. Literary fiction is a self-reflection of the human experience. When a reader takes on literary fiction, the events could represent moments related to the reader’s own unresolved experiences. Plus, some readers naturally enjoy filling in the blanks themselves because it makes them part of the story.

Colors and Covers

Another factor, though not usually decided upon until after the manuscript has been written, is the cover for the book. I find that this topic seems to go under the radar when I bring literary fiction up.

At this point, the publishing company or literary agency has sway over the design and color scheme of your novel. They may ask you for your input, maybe.

If the book you wrote is of the commercial flair, odds are the cover will be attention-grabbing. For example, an action scene from the book might highlight the cover. You will probably see weapons, too. A representation of the characters might grace the cover. Colors will vary, of course, but likely will stay with black and dark solids.

Cover designs for literary fiction will be more subtle. For example, they may display a quiet lake where the main character proposed to his wife. Sometimes, a scene of broken furniture to symbolize familial strife might appear. Lighter colors tend to own the cover. An all-around feel of a non-popular, and therefore elite, mood will promote itself to the on-lookers.

Exceptions: Respect and Commercial

As with anything else, there are exceptions to the rules.

Sometimes, novels come along that has merged its literary merit and commercial traits successfully. This does not happen too frequently, but it does happen.

Let’s look at the 1898 H.G. Wells uber-classic, War of the Worlds.

Let’s look at the 1898 H.G. Wells uber-classic, War of the Worlds.

If you wish to classify it as science-fiction, I will not disagree. It is about invading-Martians and their tyranny upon the United Kingdom. As an English teacher, I had taught this novel many times. While the science fiction element is obvious, Worlds stands the test of time because of its subtext and theme.

Wells was no average writer. He brought science, military dominance, and most importantly, religion, to a head in that novel. These metaphors brought to life various issues important to the writer at the time. Worlds is more than a plot-driven alien book. It still has critical relevance to this day.

Another novel that does something similar is the 1933 horror novel, The Werewolf of Paris, by Guy Endore.

Akin to Wells’ science fiction novel, Endore decided to use a fantastical element. He used a monster and the backdrop of war to tell the horror story. Only on the surface is Werewolf an actual monster narrative. It is so much more. The mega-success of the novel was not a surprise. If he had written a straightforward political story it may have not had the same immediate and long-lasting effect. But by successfully sewing in themes, it transcends the typical horror novel and qualifies as literary fiction.

Final Thoughts

With the surge of supernatural films adapted from novels, I don’t see literary fiction becoming the dominant genre.

I encourage my readers always to seek more information on the subject of literary fiction. It is not that commercial fiction and literary fiction are so entirely different than they are unrecognizable to one another. Rather, they overlap, owning more characteristics in specific respects that ultimately garner the appropriate definition.

Then, go to this link to see a great video about literary fiction.

~M