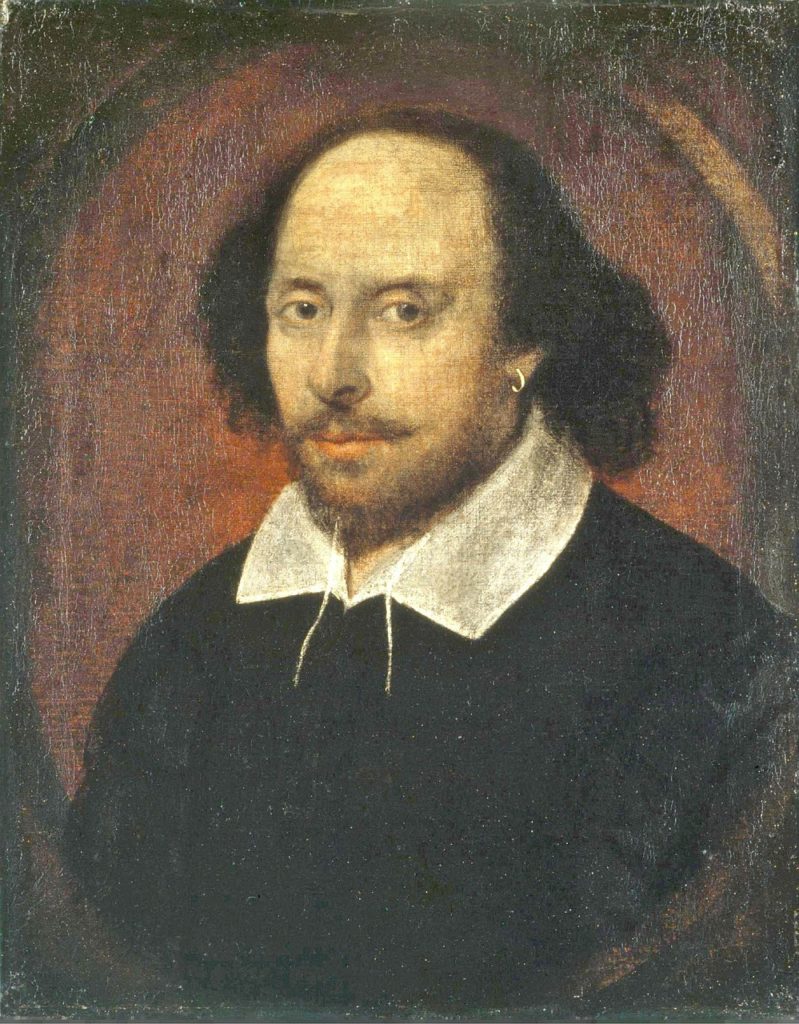

An author’s decision on how to show or when to tell information is equally as critical as Hamlet pondering suicide (“To be or not to be”). If used incorrectly and at the wrong times, it could mean literary death for the author’s story. Surely, showing and telling is not a new argument to any non-novice writer, but let’s discuss why the rule is so enforced in fiction.

The answer to show and tell in literature resides in the artistic medium. In film or stageplays, the showing is done through the visual actions of the characters. The telling is done through dialogue. In literature, the visual element is not available, so the author must reveal through subtext, the actions of the characters, the description of the settings, inner monologue, and dialogue. Telling through dialogue, as minimal as it is in most literary fiction (though popular fiction is unfortunately saturated with pages of pointless dialogue), also should be through subtext. Great artwork (literature) is at its best when the subtext (especially in dialogue) is thick, making the reader think critically for the answer. If done correctly, then the author used his or her technique of showing and telling in the right manner.

How to Show

Throughout my research on the subject, I found that writers tend to make this concern more difficult than it is. The term “showing” confuses them because they cannot seem to reconcile a technique so synonymous with vision done through mere sentences. As a result, they shift away from their intended goal of simply providing a good narrative. This shift isn’t difficult if a writer acknowledges the critical moments.

The best process is to complete in-full your chapter or story. Once finished, go back and examine any moments that could expand. Possibly, there are times when a scene ended too quickly or a character’s conversation could go deeper. An editor of your manuscript will likely tell you the same.

Show the Action

Limit the actual speech and instead detail physical action. I don’t necessarily mean walking, running, and shooting. I am referring to the specific action that moves the plot forward or creates tension. For example, if two characters are arguing in a house and one left abruptly, don’t have the one remaining inside just stand there and contemplate suicide. Instead, make that character throw a fit or involve somebody else by yelling out the window. Make those thoughts realistic and external, and you will see a huge reaction from the reader.

Don’t use any Dialogue

This is similar to the above example. If a character is happy or sad or mad, put their feelings into action without saying a word. Show them taking a walk in the park as they notice the birds and squirrels. If sad, show them looking through an old photo album or pictures of their loved ones on their cell phones. When they are mad, it should be easiest to show action. Have them take out their anger on nearby objects.

Use Dialogue

This is a chance to progress your plot and display great characterization. It is all too easy to simply state what a character will do next when in conversation. Break this by making it covert. Use slang, acronyms, nicknames, etc. Lather on the subtext in dialogue. It is not easy to do, but it can be done.

We do it every day in real life. If we don’t want others to understand what we are talking about, we will use code words and various verbal inferences to get our point across to the other party.

When to Tell

I realize the intention is to show and not to tell. And 95% of the time, I fully agree.

However, somewhere and sometime in the midst of your story, you will (un) consciously write exposition. The influential powers that be in the writing community might criticize this, but sometimes it must be used.

Hear me out.

Prologue and epilogues are notorious for telling. Their mere existence serves a purpose to inform the reader of events before and after the primary narrative. Also, sometimes authors who write serial novels and sagas may touch on events that happened in previous books. They do this so the reader isn’t completely in the dark about plot and characterization.

And this sudden exposition can happen at any time during the story. However, I do have one important suggestion: if you do use a “telling” moment in your novel, I advise you to do it at the beginning (preferred) or middle. The story hasn’t hit an extreme climax at that point and could still benefit from the exposition.

Suddenly transitioning to “telling” in the third act in literature is dangerous.

The reader has invested so much of their attention to reaching the final chapters for it to suddenly revert to anything but progression. Furthermore, these are the pages where the author should highlight their writing talents by merging plot and character together for one final explosion of revelations. Telling in the third act will only throw water on that fire and more than likely take the reader out of the experience.

*In a film, a third act regression to “telling” or flashback, etc. is different and more acceptable because a film is a visual medium that can explain quickly and thoroughly.

If you must

If you absolutely must rely on scenarios of “telling,” then do so briefly. And I mean a few lines per chapter. If an editor comes to you with issues of too much “telling,” explain to them why you think it is necessary and ask how he or she would fix it.

Wrap it up

Showing vs. Telling is a fight that every author goes through on a first draft–maybe even the second draft, too. The point is not to see it as a negative. If you or your editor find places where you tell instead of show, take that as an ideal opportunity to shine. Don’t automatically cut it from the manuscript because sometimes it is necessary. Think of its power to the progression of the story and then decide. Turn it inside-out and make it reveal something new about your characters. Have it foreshadow something that will happen in the third act.

If the dialogue is in need of fixing, take a moment and think of different ways of saying the conversation. Maybe if a different character says those words, you might discover a better way of applying subtext.

For those weary of majoring in creative writing in college, read this to strengthen your choice. If you want some advice to write realistic characters, click here. And for anyone in need of a quick grammar update, you can check this out.

Check out this site here for valuable writing info.

~M